NHS Sports Hall Of Fame: William “Red” Moulton

Published:

April 22nd, 2022

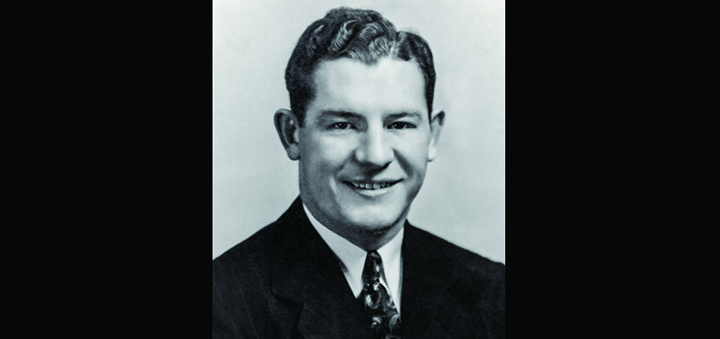

William “Red” Moulton. (Submitted photo)

William “Red” Moulton. (Submitted photo)

Editor's note: Today's article on William “Red” Moulton is the sixth in a series profiling the Norwich High School Sports Hall of Fame 2020 and 2021 inductees. A combined ceremony for each induction class is scheduled Saturday, May 14 at the Norwich High School Gymnasium at approximately 6:45 PM. A social hour begins at 4:30 p.m. with a buffet dinner at 5:30 p.m. Tickets are $20 per person for the social hour and buffet dinner, and are available for purchase at the Norwich YMCA or the Norwich High School athletics department. There is no charge to attend just the induction ceremony.

By Jim Dunne, Sun Sports Contributor

In looking over the list of captains of Norwich High School football teams since the first in 1893, there appear to be only two father/son combinations. They are Harold Moulton in 1907 and his son Bill Moulton in 1934, and Claude Cooper in 1930 and his son Don Cooper in 1964.

This is about the son in the first combination, Bill Moulton. In an era when most boys had a nickname, Bill was known as either “Dutch” or “Red.” The former was inherited from his father, Harold, who was called “Dutch” from his high school years and later.

In the 1942 NHS Football Program, Coach Beyer wrote a story about the expansion of varsity sports during the prior 15 years, from 3 sports to 8, and from 27 letter-winners to 71. Winning a varsity letter in the Beyer years was not easy, and it meant that you had been a substantial contributor to the team and had played in most of the games. Then, he provided a list of the boys who had won three letters in one year. Not surprisingly, the list was led by Salvatore “Toots” Mirabito. In second place was Bill Moulton, who had won a total of 11 varsity letters during his high school career. Beyer’s comment was, “These boys are the real honor athletes of our school. In recent years, no student has approached either of these records.”

Bill, a big, handsome guy, preferred to be called “Red,” which of course came from the color of his hair. Nevertheless, we have an Archive in which he signed his name “Dutch Moulton.” His father, Harold, was the original Dutch, and was captain of the 1907 football team, which had a record of 2-3 and George Bliven as coach, following a year in which there was no team. Harold had two brothers, Con and Cliff, who may be remembered by some. Their father was Will Moulton, a lawyer who came to Norwich, having practiced before in New York City.

In the 1944 NHS Football Program, Coach Beyer included a table which listed those who had earned four varsity letters in football since Beyer’s arrival in Norwich in 1930. There were seven names, including Bill Moulton in 1931-34. (The others were Dick Lyons 1929-32, Wilmer Wells 1930-33, Carl Hughes 1932-35, Angelo Zeino 1933-36, Sal Mirabito 1934-37, and Stan Burdnell 1935-38.)

In addition to the 4 letters in football, Moulton earned 3 letters in basketball, 2 in baseball, and 2 in tennis. He was the football captain in 1934, basketball captain in both 1933 and 1934, and tennis co-captain in 1935.

The football record for the three seasons that he started at end was a combined 17 wins, 7 losses, and 1 tie. In 1932, the only loss was to Binghamton, in a 7-1 season that saw Norwich outscoring the opposition 189-58, and finishing in a tie with Ithaca and Union-Endicott for the Southern Tier Conference championship. In a season of close games, 1933 had wins over Ilion, Cooperstown, and Cortland, and losses to Johnson City, U-E, and Canastota, with a 6-6 tie with Bingo.

The 1934 season, with Moulton as captain, produced some of the most memorable games in NHS history, especially the victories over Johnson City and Bingo.

In the 1943 football program, Coach Beyer listed 14 of his favorite memories of past teams. One was this: “That across-the-field lateral pass from Dutch Moulton to Harold Frink in 1934, against Johnson City, leading directly to a 14-13 upset victory.”

In looking up Perry Browne’s account of that game, it became clear that the play occurred during the return of a Johnson City kickoff, and so the pass would be legal only if it were a lateral:

“Cutting deep into Norwich territory in the first quarter, the Johnson City gridders were successful in scoring on their second challenge. The goal point was missed. Stirring his men to full power, Captain Bill Moulton and his cohorts lined up to receive the kick and every man was bristling with fight. Moulton received the shoetown kick on his own 10-yard line and returned it to the 25-yard chalk stripe. There he tossed a perfect lateral to [Harold] Frink, who having outsmarted the defense, broke loose to jaunt to the JC 26-yard line. Two line-bucks took the pigskin to the JC one-yard line and then, on a fake buck, a lateral to Captain Moulton and he went across standing up. A pass, Frink to Moulton, converted the extra point. The lateral pass that paved the way for the Norwich touchdown brought the 2,500 fans to their feet and it goes into the records as the most thrilling play Triple City fans have seen this season in interscholastic competition.”

The game ended in a Norwich upset 14-13, after Moulton intercepted a JC pass and took it in for a second touchdown. It turned out to be an important upset, because it gave Norwich a tie with Cortland and Johnson City for the championship of the Southern Tier Athletic Conference, consisting of Oneonta, Cortland, Johnson City, and Norwich. It also put an end to Johnson City’s hopes for an undefeated season. The following week, Norwich lost to Cortland, 9-6, and thus, Cortland had lost to Johnson City, Norwich had lost to Cortland, and Johnson City had lost to Norwich – a 3-way tie.

For the season, Norwich finished with a record of 7 and 3, including a 6-0 triumph over Binghamton. That game was also one of Beyer’s favorite memories, featuring as it did a series of defensive stands through most of the fourth quarter. Captain Moulton was not present for the Bingo game, having to take a qualification test for admission to West Point, but Beyer credited his leadership for the team’s defensive stands to preserve the victory. One of his favorite stories was about a stranger who approached him after the game to shake his hand and tell him the Norwich defensive stand was the greatest example of courage he had ever seen.

Basketball at Norwich during the 1930s was a different story. Whereas football won 75% of the games, basketball won 25%. For most of those years, 7 of 10, Beyer was the coach. He admitted that basketball was not his forte, and in 1940 he brought Hal Bradley in to turn the program around. In the two years that Moulton was captain, the records were 4-12 and 3-12. Moulton himself, however, was chosen for the All-Conference team and led the league in points scored, and in Tom Rowe’s monumental collection of NHS basketball statistics, he stands ninth in scoring for the decade of the 1930s.

To begin the 1933-34 basketball season, the starting 5 were known as the “Iron-man team” because they played the entire game without substitutions. They were Moulton, Harold Frink, Ron “Nig” McIntyre, Pete Ruffo, and Tom Natoli. Moulton and Frink were injured early, but once they came back, Norwich won the next 2 games. However, after that, Ruffo was declared scholastically ineligible, and McIntyre moved to Hamilton with his family. Juggling the line-up, Beyer moved Moulton from center to forward, and inserted tall sophomore Paul Rice into the center spot; the result was that neither scored as much as Moulton had at center. Then, Bill missed a few games at the end of the season, as his mother was taken ill with scarlet fever. She died on March 25, 1934, at the age of 36.

In reviewing the all-conference team, Beyer said of Moulton, “Bill was by far the outstanding player on the Norwich team during the greater part of the season. An excellent ball handler and shot maker, Moulton was a relaxed player at all times. Handicapped by the constant change of teammates, his play was of very high order in every game in which he played. He rates very high on defense as well.”

After lettering for two years on the baseball team as catcher and third baseman, Bill decided to spend spring on the tennis courts. Whether that was his own decision or at Beyer’s request is lost in the sands of time, but the athletic director was known for balancing his teams to achieve the most victories.

In his first year on the courts, playing at #2 behind Captain Max Gustafson, who was completing his fourth year of varsity tennis, the rookie Bill Moulton competed strongly but lost most of his matches (Hancock 6-4, 8-6, Oneonta 9-7, 7-5, Hancock 6-4, 7-5, Oneonta 5-7, 6-4, 6-3). Some matches were not reported by the Sun.

In the second year, George Stone, who had always been Norwich’s best player but had been ineligible for academic reasons, took the #1 spot, and Moulton continued at #2. In 1935, Norwich competed in the eastern division of the Southern Tier League, playing Oneonta, Hancock, and Walton each twice. Walton had won the league championship the year before, and provided the stiffest test for the Purple. Norwich won both matches, 3-2 and 4-1, handing Walton their first defeat in two years.

That year, 1935, Norwich won all its dual matches, giving purple tennis its first undefeated season. Both Stone and Moulton won all their singles and doubles matches, neither losing a set. The final match of the league was against Binghamton, which had captured the western division, winning over Owego, Cortland, Johnson City, and Endicott.

Again in the singles, Stone and Moulton did not lose a set in taking their matches. Against Bingo’s two best in the doubles, with the meet score standing at 2 and 2, here’s Perry Browne:

“Norwich won the first set 6-3 but Binghamton resorted to a lobbing game to throw the Norwich boys off stride in their driving and smashing play. The result of the strategy favored the Blue and White and they won the second set 6-3. In the third set Norwich took the lead at 3-1. Bingo tied the count at 4 all. Norwich won the next game on Moulton’s service after a hard fight over a deuce game.

“In the final game, Moulton put away the first point and then dropped one over the net for the second. Stone slipped one down the alley for the third. On the final and decisive set, match, and meet point, Stone reached the peak of his play to smash a high lob deep into the opponent’s court for a positive point and victory. It was as brilliant a display of scholastic tennis all the way through as one could hope to see.”

Stone and Moulton were entered in the Section IV doubles. They defeated the teams from Walton and Watkins Glen, and then met Owego, who had defeated Ithaca and Binghamton, in the finals. They won that match too, becoming Norwich’s first tennis sectional champions, without dropping a set.

That ended the high school athletic career of Bill Moulton. He had taken the post graduate year in hopes that there would be a way for him to continue in college. His mother had passed away while he was in high school, and his father was a lineman for the phone company. A letter dated August 17, 1935, informed Bill that he was to receive a scholarship from the New York State Elks Association Scholarship Committee. It was the only award given by the NYS Elks, and would probably pay his tuition, room and board for at least two years. It was signed by Frank R. Wassung, chairman of the state Elks committee, and stated “You were easily the outstanding candidate.” Within a month, Bill was a freshman at Cornell University.

In high school, he had good marks and had been active in dramatics and student council, had been president of Chi Alpha, and was voted “most versatile.” At Cornell, he took his freshman year to become acclimated, and joined Sigma Nu, a leading social fraternity. In his sophomore year, he went out for football.

His first year of football coincided with Carl Snavely’s first year as Cornell head coach. It was the beginning of “The Golden Age of Cornell Football,” before the formation of the Ivy League put a damper on athletics in favor of academics. In 1936, the “sophomore team” lost to Yale, Columbia, Princeton, Dartmouth, and Pennsylvania, but beat Syracuse and Penn State. Bill Moulton played in every game, catching and intercepting passes and blocking for the shiftier running backs. He sometimes found himself on the opposite end from Jerome “Brud” Holland, Cornell’s first “Negro” football player, and an All-American in 1938 and 1939. Moulton was awarded the block “C” at the end of the season.

In 1937, Cornell’s record improved to 5-2-1, and culminated in an undefeated season in 1939, when they were named National Champions, beating Syracuse, Penn State, and Ohio State.

Moulton played again in 1937, when he was a junior. Again, he was active in every game. Cornell started the season with wins over Penn State, Colgate, and Princeton. They were favored in the next game against Syracuse, when George Peck, their star running back, was diagnosed with a chipped vertebrae, and Moulton was moved from end to start at his position.

Cornell lost to Syracuse, 14-6, and the Ithaca paper concluded that, “All-in-all, the Syracuse team was very much under-rated and Cornell very much over-rated.” What really made the difference was the presence of a “flea-sized” back named Marty Glickman, later to become a renowned sportscaster, in the Syracuse backfield. He scored both touchdowns and repeatedly left Cornell defenders in his dust. The Ithaca paper, master of the understatement, reported that “Bill Moulton performed more than creditably.” Late in the first half, he intercepted an Orange pass, and it appeared that the tide had turned, but it was not to be. The Ithaca sportswriter Ken VanSickle reported that “Red Moulton wore two jerseys – no. 64 was ripped so badly that his shoulder pads flopped loosely – he finished with no. 62.”

Throughout his time in Ithaca, Bill had worked at jobs that ranged from handing out samples of Chiclets to scrubbing pots and pans at a sorority to working in the kitchen of his own fraternity. Money had always been tight. In a homespun autobiography that he gave to his daughters, he describes what happened at the end of his junior year:

“I received word that my father was ill in the hospital with a ruptured appendix. Of course I went home right away. It was a serious situation because peritonitis was infecting Dad’s system. I guess they didn’t have antibiotics to treat it. Dad passed away after a week of being very sick. The next unpleasant situation was that my college career was ended – there was no more money.”

Jobs were hard to find in the country still reeling from the Great Depression, but Moulton landed a job with F. W. Woolworth, and after a few years, with Pan American Airways. He advanced at Pan Am, setting up branches in several countries, and retired as an executive in 1976. In retirement, he continued to be active, working in security for Lord & Taylor. His last years were spent in assisted-living, but he was never sickly or mentally-deficient. He was sharp, alert, and always helpful to his fellow residents, even giving pool-shooting lessons on Wednesdays. He passed away in January of 2010 at the age of 94.

Comments