NHS Sports Hall Of Fame: Clarence “Jock” Taylor: Class Of 1923

Published:

March 24th, 2023

The Norwich High School Sports Hall of Fame is happy to announce its 2023 class of honorees which includes five athletes – Clarence “Jock” Taylor, Dick Harrington, Ken Stewart, Jim Ward, Johanna Schultz Dalton – and one contributor – Francisco “Frank” Speziale. An in-depth biography of each of the six inductees will run Fridays in The Evening Sun.

This year’s event will be held at the Norwich High School gymnasium on Saturday, May 6 with a buffet dinner at 5:00 p.m., followed by the induction ceremonies at approximately 6:00 p.m. Tickets to attend are $20 and can be purchased at the front desk of the Norwich YMCA or the Norwich High School Athletic Department by phoning 607-334-1600, ext. 1139. Those wishing to attend just the ceremony may do so free of charge.

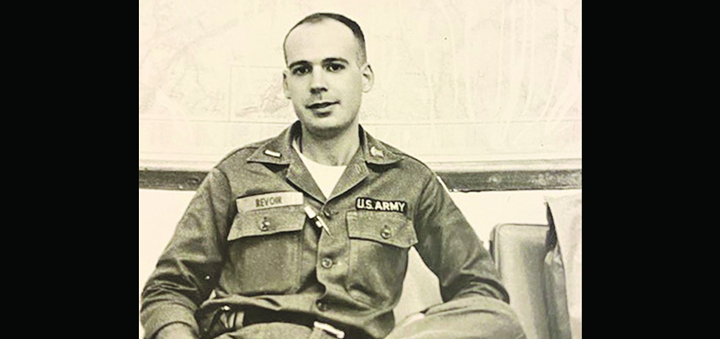

Clarence “Jock” Taylor: Class of 1923

By Tom Rowe

Perhaps as a young Norwich High School sophomore, Clarence “Jock” Taylor took in one of 1921’s most popular silent films, “O’Malley of the Mounted.”

The film, starring William S. Hart as Sergeant O’Malley of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, tells the story of O’Malley’s heroic actions in the Northwest Territories, while trying to stem the tide of men who dare follow their own impulses rather than obey the law. Needless to say, he not only wins out against the “bad guys” but wins the heart of Rose Lanier, who is played by Eva Novak, an actress who appeared in 123 movies over her 47-year career. Novak’s second-to-the-last film was the much-acclaimed “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” in 1962.

Forty years later, the premise of that movie was used in the animated cartoon “The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show,” where the fictional character Sergeant Dudley Do Right was first introduced as the main protagonist of the Canadian Mounties. You might say Taylor was two generations ahead of himself, because he always did right.

Taylor, who graduated two years after that silent film’s debut, never needed to venture north of the border to achieve success. But, as an NHS student/athlete, he emulated the heroic deeds of Sergeant O’Malley in a variety of ways. Not only was he a gifted and talented athlete, earning 11 varsity letters in football (4), basketball (4) and baseball (3), but he was president of the Norwich High School Athletic Association (1922-23) and a charter member of Chi Alpha (1921-23), the school’s National Honor Society chapter.

Because of this compilation of accomplishments, he has earned his rightful place among the Tornado greats as one of the six newest inductees into the 11th annual class of the Norwich High School Sports Hall of Fame.

A gifted athlete in every sport he played – football quarterback and fullback, basketball point guard and baseball third baseman – Taylor was glowingly lauded in the 1923 Norwich Archive with these words of praise, “Without doubt “Jock” is the best all-around athlete the school has ever had. If we were to give his characteristics we should speak of his love of fair play, his good nature, certainly tantalizing to his opponents, and above all his ‘never say die’ spirit.”

His greatest athletic achievements came as a four-year starter on the Purple basketball team. During those winter seasons of long ago, Norwich compiled a gaudy record of 71-9-1 (.888). Taylor, who directed the hardwood five from his point guard position, was a member of both the 1919-20 New York State championship team and the 1920-21 NYS runner-up club. Those two successful teams went 40-2-1, winning 37 straight at one time between Feb. 6, 1920 and March. 31, 1921, a record that still stands and shared with the 1992 and 1993 fives.

In addition to being the Norwich captain his senior campaign, Taylor amassed 329 points during the 1920s, a total that is fifth best for the decade, even though he was best known for his tenacious defense. He was honored by the Binghamton Morning Sun by being placed in the right guard berth on its mythical first team of the Southern Tier Interscholastic Basketball League.

“Taylor is one of the fastest guards in the circuit and is a strong man on either defensive or offensive play, and is a basketeer who is able to use ‘headwork’ in his game as well as basketballism. In the early stages of the season just ended, it was Taylor in a large part who was relied upon to hold down the scoring machine of opponents, and as the season advanced and the Norwich quintet became crippled, it was Taylor who acted as pilot, a wise leader, a consistent basketball player, a defensive player that was near the border of perfection,” read the article.

“As a pure defensive man Taylor lacks a peer in either northern, central or southern New York. On the offensive side of the game his ability for team work was excellent, his ability to pass was excellent and his ability to locate the net was just as good. Whenever the game reached its climax and Norwich was hard pressed, Taylor was the man on the (Coach Lew) Andreas quintet to pull his team mates through the crisis.”

While basketball was truly king of the city with crowds numbering in the several hundred at local contests, both football and baseball had to take a backseat. During Taylor’s four years on the gridiron, the Tornado 11 compiled a record of 19-12-2 (.613). And baseball, after a seven-year hiatus, was revived just in time for Taylor’s sophomore spring, during which time he was elected captain. As would be expected, the NHS nine did not illuminate the city with any fanfare as they rang up a three-year log of 11-11.

Although football had been played by Norwich since the fall of 1893, it had not attracted the notoriety that its winter cousin, basketball, had. That began to change in 1921 when Lew Andreas took over the Tornado reins, after graduating from Syracuse University. A native of Sterling, IL, Andreas played one year for the Fighting Illini before transferring to Syracuse.

Defense was the hallmark of that first Andreas 11 as Norwich, despite a 5-4-1 record, outscored its opponents 173-47 with six of those 10 outcomes a Purple shutout. Those four defeats were by a mere total of 28 points – Union-Endicott (19-6), Cazenovia (14-7), North Syracuse (7-6) and the Colgate Collegians (7-0), and the Cortland contest resulted in a 0-0 tie.

Taylor, who mainly played fullback his first two falls under Coach Clinton Blume, was shifted to quarterback with the arrival of Andreas. Through Norwich’s first six outings, Taylor scored seven touchdowns, one via a 25-yard interception, and added three extra points.

Unfortunately, on Nov. 12, he suffered a fractured left arm during that loss at North Syracuse. He still received postseason honors, though, when he was named an honorable mention selection by Chester B. Bahn of the Syracuse Journal on the All-Central New York team.

From fullback his first two falls, to signal caller his junior season, Taylor moved again at the beginning of his 1922 senior campaign to right halfback. The change did little to affect his worth as he produced four TDs through the first six games, saving the best for his final two outings as Norwich chalked up a 6-2 success log.

On Saturday, Nov. 11 during the season’s final home battle with Johnson City, he ran back a punt return 80 yards for six points, caught another TD pass from Glenn “Tommy” Manning, added two extra points and blocked a JC punt attempt as Norwich won going away 39-0. The following weekend, he returned one last time to his quarterback slot and tossed a 30-yard scoring spiral to Luke “Farmer” White as the Purple produced their fifth shutout of the year with a 6-0 blanking of Christian Brothers Academy at Schiller Park in Syracuse before an overflow crowd of 3,000.

Norwich Sun sportswriter Perry Browne sang Taylor’s praises in an article in the local paper’s Nov. 28 edition. “Among those players who must be seriously considered for mythical positions on all-scholastic elevens are ‘Jock’ Taylor, a plunging hard hitting halfback.”

Browne’s words were well taken by sports writers throughout the state because Taylor was tabbed a second team All-State pick following his senior fall to go along with his honorable mention status of a year earlier.

While basketball and football brought much notoriety not only to Taylor but his Norwich teams in general because of his athletic leadership, he may have been at his best on the baseball diamond, despite the Tornado’s lack of success. A three-year letterman, who captained the Tornado nine his sophomore spring, Taylor went hitless in only one of the Purple’s 22 contests.

The only reason Taylor did not letter four years in baseball, like he did in basketball and football, was because the sport was not fielded his freshman year. Having not been played since 1913, the game resumed in 1921 with Dr. John C. “Bot” Lee as the coach. Lee, a 1910 Norwich High grad, had played center field while in college at Fordham University.

Taylor, who batted third and played third base, put up some gaudy numbers that spring, going 20-for-48 for a .417 batting average with 17 runs scored, two triples and one double as the Tornado went 8-3. The next year under Andreas, he remained zoned in with a .412 average (7-for-17) with five runs scored, three two-baggers and a pair of stolen bases. He subsequently saved his best for last as he batted .550 (11-for-20) with 10 runs scored, three doubles and two more stolen sacks during his final athletic season in the Purple & White. All told, he produced a three-year batting mark of .447 (38-for-85).

The following year, after Taylor’s graduation, baseball was again dropped in favor of only track and field in the spring of 1924. It was revived the next year under Coach Reaves “Ribs” Baysinger and has remained uninterrupted ever since.

Taylor, meanwhile, attended Suffield Academy in Suffield, CT following his graduation from Norwich High School. There, he again starred in football at a school with a stellar history. He once jokingly said, “I was out for a team whose roster contained 22 ex-high school football captains.”

After his stint at Suffield, he went on to Syracuse University where he continued to excel on the gridiron on teams during the era of Vic Hanson, a consensus All-American in 1926. During Taylor’s time at SU, the Orange compiled a record of 20-6-4 (.769), going 8-1-1 his senior year when he was reunited with his old NHS mentor Andreas, who was in his first of three years there.

Upon graduation from Syracuse in 1928, he joined a pair of utility firms in the Midwest and Long Island before relocating to Oneonta in 1948 to take over the management of the city’s brand-new water plant. In 1950, he was named Director of Public Service, a position in which he was responsible for the Water Department, its modern filtration plant and various programs of the Department of Public Works. He was cited several times by state and national officials for his work as a water department superintendent and was president of the state water superintendent’s organization.

An article in The Daily Star acclaimed his worth to the City of Oneonta. “Evidence of his dedication to his post is legion throughout Oneonta, including the athletic plant at Neahwa Park, the swans in the park pond, and, on a personal level, the young Oneontans who he has guided along paths to higher education.”

Frank Perretta, The Daily Star Editor, penned another article detailing how much Taylor meant to Oneonta. “It wasn’t strange to see foreign mail on his desk at the Oneonta water plant for ‘Jock’ Taylor had become one of the most respected water treatment specialists in the nation. He was active with the American Waterworks Association and his ideas were transmitted to some of the most remote spots in the world. He once received a letter from a Japanese operator, whom he had counseled. It was signed ‘your protégé.’”

But Taylor was more than an Oneonta Water Department employee. For many years he assisted Oneonta High School coaches in scouting and advising them from a high vantage point during the games. He offered advice, merely suggestions, no orders. And his graciousness was accepted not only by the coaches, but the young men who played football.

“Jock had the patience of Job, and that’s what his job needed,” added Perretta. “He had patience with the many students who toured the water plant; he had patience with city officials who often were more worried about the cost of pumping water than its quality; he had patience with the politicians who needed a headline so they started picking on city workers; he had patience with cub reporters who often asked stupid questions.”

For years baseball players and football men chafed because of the bumps and low spots in the ball field at Neahwa Park. During football season, the second base area was the 40-yard line and it caused havoc with breakaway runners, because every time it rained the water gathered in the low places out beyond second base.

Taylor, prior to the start of the 1957 spring baseball season, explained how he and his crew alleviated the situation. “We took all the sod up and moved a road scraper in on the entire infield. Then we leveled it off and pushed the soil toward the low spots. All along the outer fringes of the infield the dirt was spread out making the infield look twice its normal size. We then resodded the infield and planted grass in the area outside of the infield.”

The transformation was almost instantaneous. Long-time Yellowjackets baseball coach Hal Hunt remarked that the field was in the best shape in his 29 years of coaching at Oneonta.

So, it was no coincidence when Taylor was tabbed the toastmaster a few years later when the city honored the 1960 Yellowjackets 11 in becoming the first undefeated and untied team in the school’s 35-year football history at a testimonial dinner at the Eagles Club. In addition to presenting OHS grid coach Lloyd Baker with a plaque commemorating the occasion, Taylor, because of his Syracuse ties, was able to commandeer the likes of hometown favorite Denny Weir, John Mackey, Pete Brokaw, John Brown and Roy Simmons to speak at the ceremonies.

“Jock was always helpful and accommodating with whatever you asked of him,” recalled long-time Oneonta Athletic Director and boys’ basketball coach Tony Drago, whose 1959-60 cagers preceded the gridders by a few months in claiming the Section III championship. “It was an honor to have known him.”

Because of his public works employment and dedication to Oneonta athletics, Taylor’s legacy may loom larger in the Otsego County city than in his birthplace. Born in Norwich on Aug. 11, 1904, he was the second of two sons to Charles R. and Ida (McComb) Taylor. Raised at 39 Hayes Street in the city, his parents owned and operated Taylor Confectionary at 69 North Broad Street. That building, on the corner of North Broad and Henry Streets, later became (Julian) Taranto’s IGA Grocery Store before being raised in the 1970s for the Treadway Inn.

Two years after graduating from Syracuse, he married the former Dorothy Gunther on Aug. 20, 1930 in Joliet, IL. Together they were blessed with a son and daughter, Frederick C. and Terry. Fred resides in Chula Vista, CA, while Terry (Govoni) died in 2005 in Medfield, MA.

Taylor, meanwhile continued his position with the Oneonta Water Department until his death on April 6, 1969, following complications from partial amputation of his left leg. If not for his demise at age 64, he still had one more goal to conquer – Mayor of the City of Oneonta.

Oneonta Star writer Perretta recalled “Jock’s” dream. “He became ill and talked of retiring. He never did, but he spoke of it with enthusiasm – not the enthusiasm of a retired man who wants to fish and loll in the sun but with the enthusiasm of a man with a new goal.

“He wanted to be mayor. And he could have easily become mayor for he had many friends, supporters and people who respected his willingness to serve and his intellectual capacity. I have no doubts that “Jock” would have made an excellent mayor. Too bad time ran out before he had the chance.”

By now readers are probably wondering why Clarence M. Taylor was called “Jock.” Although I have researched and read every available story on him, there has never been a mention of his nickname origin. He obviously was a talented and gifted athlete, but that scenario does not seem to play out.

Perhaps his son Fred’s remembrances offer the best motive. “He did not like to be called Clarence. He’d sign everything C.M. Taylor or ‘Jock’ Taylor. I don’t think he signed anything Clarence Taylor. I assumed it came from his father, who was also called ‘Jock’ but that is just a guess.”

Whatever the reason for his unique nickname, this June marks the 100th anniversary of “Jock’s” graduation from Norwich. In retrospect, he left Norwich as one of its most decorated athletes as well as students, went on to more success at Syracuse University and finished his life-long work in Oneonta as the city’s Water Commissioner. And he was the confidant and friend to everyone in that Otsego-county burg.

What more can you say about a man who always seemed to Do Right!

Comments